Giant tortoises are being released again on Floreana Island, more than 150 years after they disappeared from the island. The return is part of a long restoration effort led by the Galápagos National Park Directorate and the Galápagos Conservancy, with satellite support from NASA. Scientists are using Earth observation data to decide where the animals are most likely to find food, water and suitable nesting ground. The approach combines climate records, vegetation mapping and years of field observations. On 20 February, 158 tortoises were released at two locations on the island. Conservationists say the goal is not only to reintroduce a species once lost there but also to rebuild ecological processes that shaped Floreana for centuries.

NASA: Tortoises vanished from Galápagos after hunting and invasive species spread

Tortoises once moved freely across Floreana. In the mid-nineteenth century they were heavily hunted by whalers who stopped in the islands for fresh meat. At the same time, pigs and rats introduced by ships began eating tortoise eggs and hatchlings. Over time, the local population collapsed.Their absence altered the landscape. Giant tortoises graze on vegetation, press paths through thick growth and carry seeds in their digestive systems from one place to another. Without them, plant patterns shifted. Some areas thickened. Other zones changed more slowly, almost unnoticed.

DNA evidence linked living tortoises to extinct Floreana lineage

The return has roots in an earlier discovery. In 2000, researchers working near Wolf Volcano on Isabela Island found tortoises that looked unusual. They did not match known living species. Later, DNA taken from museum bones and cave remains showed that some of these animals carried ancestry from the extinct Floreana tortoise.A breeding programme followed. Eggs were collected, and young tortoises were raised in controlled conditions. Over the years, hundreds have been produced. Many are now large enough to survive in the wild. Scientists believe whalers may have moved tortoises between islands in the past, which unintentionally preserved fragments of the Floreana lineage elsewhere.

NASA’s satellite data guides release sites and long-term planning (image Source -NASA)

NASA’s satellite data guides release sites and long-term planning

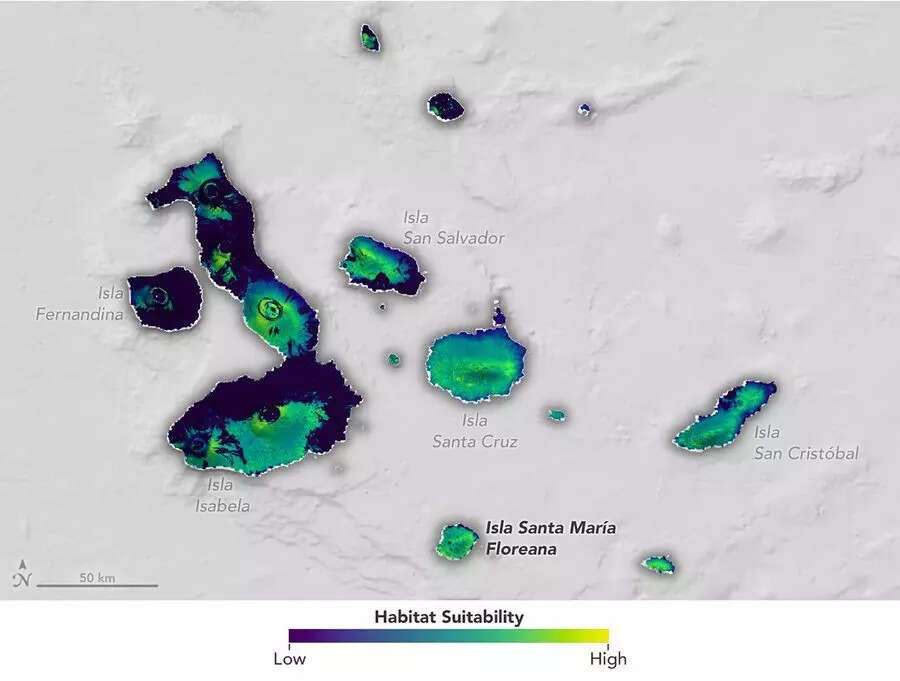

Choosing where to release tortoises is not straightforward. Parts of the Galápagos are cool and damp where hills trap cloud cover. Other areas remain dry for much of the year. Tortoises travel between these zones, sometimes over long distances.NASA satellite missions such as Landsat and Terra provide data on vegetation cover, rainfall and land surface temperature. These records are combined with millions of field location points gathered over decades. Researchers use the information to build habitat suitability models, estimating where conditions are favourable now and where they may remain stable in future decades. The tortoises can live for more than 100 years. Planning therefore looks beyond immediate survival. It considers how rainfall patterns and plant growth may shift over 20 or 40 years.

Floreana restoration project aims to rebuild ecosystem balance

The release forms part of the wider Floreana Ecological Restoration Project. Efforts are under way to remove invasive mammals, including rats and feral cats. The long-term aim is to reintroduce 12 native species and restore ecological balance.More than 10,000 tortoises have been raised and released across the archipelago over the past 60 years. Each island differs in terrain and climate, so decisions vary from place to place. On Floreana, the work feels measured. Animals step out slowly into scrub and grass. The outcome will take years to read.